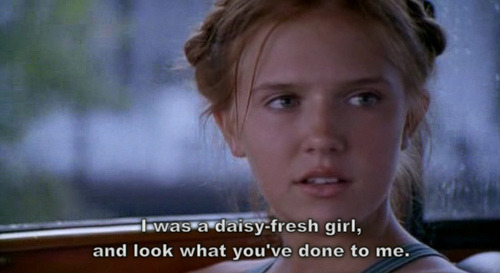

Lolita (1997)

I could be yours, I could be your baby tonight

Adult-child relationships have always been a tricky subject for films, one that seems to step beyond most peoples comfort zone both morally and familiarly. Add to this a father-daughter relationship and you’re in the realms of Freudian thinking. Lolita, originally a novel by Vladimir Nabokov, does just this so what was perhaps more intriguing was seeing (literally) its transformation into a moving picture…

The novel is, needless to say, one that does not excuse from the unfamiliarity of ‘unwarranted’ or ‘immoral’ relationships, dealing with a risqué subject at best. Both the main characters Humbert Humbert and Dolores ‘Lolita’ Haze show a strong desire for an intimacy that should be unspoken, forbidden and impossible.

Although the film is arguably tame in its visual portrayal of the sexual intimacy, the obscure obsessional desire between the father to his (step) daughter is delivered with a force that whilst making some viewers uneasy – it is not given an 18 certificate for no reason – captivates that minds of other viewers who are simply looking to comprehend such a thing.

Such a relationship evolves from what is termed the ‘electra complex’. This notion suggests a desire for a daughter, in her sexual infancy, to develop a desire to overpower the mother figure in order to replace her as intimate partner to the husband. But Lolita delves deeper than this…

What is so captivating in both the literary and film works is the way in which such a relationship is dealt with. Nabokov tips between the boundaries of maturity and innocence to create a relationship that is certainly questionable from a moralist point-of-view but also psychologically fascinating.

There are fleeting moments of delicacy amidst the ruin. The promiscuity of Dolores shows an endeavour to overcome the internal muddle of sexual strangeness. It seems hard to lightly pin-point which character is directly at fault due to the enticing allure the girls casts over the father. Indeed the ‘Lolita’ appears to relish the charm she can procure but nevertheless the viewer is reminded of her naivety by the patriarchal figure of Humbert with his (almost) menacing control.

Both characters appear at fault alternately throughout the course of the film but ultimately by the end of the film the viewer is gasping at the screen, lost for words, unable to point the finger at either. The downfall of both a fully grown man and a pre-pubescent girl seems to stun and is tragic, although perhaps not in the sense of traditional romance tragedies (Shakespeare anyone?), but still on a level that at first seemed un-doable.

What inspired me: The complex relationship between maturity and innocence. The way in which such a topic is dealt with so delicately but at the same time so boldly. The clothes worn by Dolores Haze.

Originally published 27th August 2012